I know I usually write about each individual book in a series but I read The Cruel Prince, The Wicked King, The Queen of Nothing, and How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories in such quick succession that they have all blurred together for me. The fact that I read them all so quickly is probably more than enough of a review for some of you but I actually started and ended the series a little unsure, it wasn’t until I accepted that it’s mis-sold as purely enemies-to-lovers (this is a plot point but it’s such a small part of the plot!) and that it’s YA for a YA audience (Holly Black’s writing style is so brilliant I could have mistaken it for adult fantasy if not for the ages of the characters and some of the tropes) that I realised it’s actually pretty amazing. After I finished these books I really thought I’d just forget them in the same way I’ve sort of just let go of The Grisha Trilogy but Holly Black’s The Folk of the Air has stuck with me and I can’t stop thinking of it for a few reasons;

The Fae

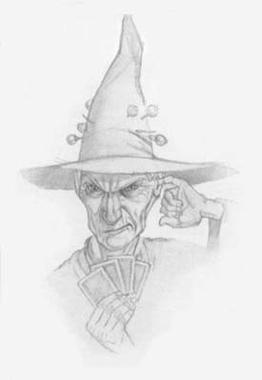

First of all, anyone who knows me will know I’m deeply obsessed with the Fair Folk, the Good Neighbours, the Hidden People, they are my jam, literally just look at my blog title, I wanna look at goblin men and Black delivers plenty of hobgoblin-y goodness for me to gaze upon. Black’s fae, or the Folk, are so close to real folklore they are horrific and believable and utterly inhuman. I know it sounds silly but I love that aesthetic of the fae in literature that isn’t particularly dark or light, evil or good, they are just a terrifying morally neutral thing that dwells in nature. For me Holly Black’s work is up there with books like Jonathan Strange and Me Norrell and Under the Pendulum Sun which are perfect examples of fae to me.

The story follows Jude Duarte, a human whose parents are murdered in front of her by her mother’s ex, the redcap and general of Elfhame, Madoc, only to be taken in and raised by him. Now Madoc isn’t the small redcap goblin we usually imagine; he is tall, but that’s the only real difference from folklore (and I’m sure there’s folklore of taller redcaps) he is green, goblin-like and does indeed have a red cap that he dips in the blood of his slain enemies. He is bloodthirsty, but he is also a father to four children, two of them human, who he raises with care and genuine affection and worry. If you couldn’t tell Madoc is my favourite character but he’s also the perfect example of how complex and interesting Black’s Folk are, they are just so genuine it’s hard not to become a little obsessed with them.

The Politics

Though I’ve spoken about the fae being morally neutral I mean that as a whole. They are not an evil race in the way orcs are in LOTR, but individually they are as morally complex as humans but without the ability to lie. How exciting is that?! Imagine Game of Thrones where no one can tell a lie except for Tyrion. That’s basically how the politics here work, everyone has to be underhand and clever with their words, except for Jude and her sister. Jude would rather live her life by the blade but her ability to lie pulls her into a tangled web of faerie politics that involves her with her arch nemesis Prince Cardan Greenbriar.

Jude and Cardan

Jude and Cardan could be the stuff of a ye olde folk ballad or a medieval epic. They are such strong and distinctive characters. Even without the enemies-to-lovers subplot their relationship is a wild ride. I can’t give away too much but every small progression of their relationship ties in so well with the rules of the Folk, their magical limitations, the relationship between the Folk and humans, it’s just brilliant. Although I wouldn’t say this series is explicitly enemies-to-lovers I can see why people focus on that arc so much Jude and Cardan are just a car crash character pair you literally can’t look away no matter how brutal it gets. I did feel like their relationship was a little rushed towards the end (in fact the whole last book felt rushed) but it was still compelling nonetheless and I think it’s a testament to Black and how she writes relationships that this small aspect of a massive plot captures everyone’s imaginations so thoroughly.

So I guess that’s my review/thought-vomit over, I loved this series and I can’t imagine any lovers of the fae or urban fantasy wouldn’t love it too. It’s probably some of the first YA I’ve read in a while that crosses over very well to adult readers too without relying on steamy romance to build that bridge, looking at you Maas!

We all know what mermaids are, sexy fish-tailed ladies with flowing locks and lovely voices who tempt sailors to their doom. They aren’t the only ones who do this in folklore, there’s sirens, rusalkas, huldras, selkies, and about a million other terrible women who are completely at fault for the men chasing them. A mermaid, like a selkie, usually has a kind of love story to go along with their tales (ha); they either pursue a human man and either succeed and gain a soul or die and turn to sea foam, or they are stolen like Selkies with magical objects like combs, pearls, dinglehoppers you get it.

We all know what mermaids are, sexy fish-tailed ladies with flowing locks and lovely voices who tempt sailors to their doom. They aren’t the only ones who do this in folklore, there’s sirens, rusalkas, huldras, selkies, and about a million other terrible women who are completely at fault for the men chasing them. A mermaid, like a selkie, usually has a kind of love story to go along with their tales (ha); they either pursue a human man and either succeed and gain a soul or die and turn to sea foam, or they are stolen like Selkies with magical objects like combs, pearls, dinglehoppers you get it.

So The Trouble with Triffids is no more folks! I’ve decided, after much deliberation to change my blog up a little, though not much I’m not really one for change. The biggest change is really the new name: Let Us Look at Goblin Men, my content will remain the same, but I will no longer feel irrationally guilty for posting anything non-sci-fi based. Anyone who’s followed this blog from the start knows it started out very heavily sci-fi, but I want to explore all speculative fiction including fantasy, horror (which I have already been doing) and even some poetry and film, and I want the blog to reflect that a little more.

So The Trouble with Triffids is no more folks! I’ve decided, after much deliberation to change my blog up a little, though not much I’m not really one for change. The biggest change is really the new name: Let Us Look at Goblin Men, my content will remain the same, but I will no longer feel irrationally guilty for posting anything non-sci-fi based. Anyone who’s followed this blog from the start knows it started out very heavily sci-fi, but I want to explore all speculative fiction including fantasy, horror (which I have already been doing) and even some poetry and film, and I want the blog to reflect that a little more.